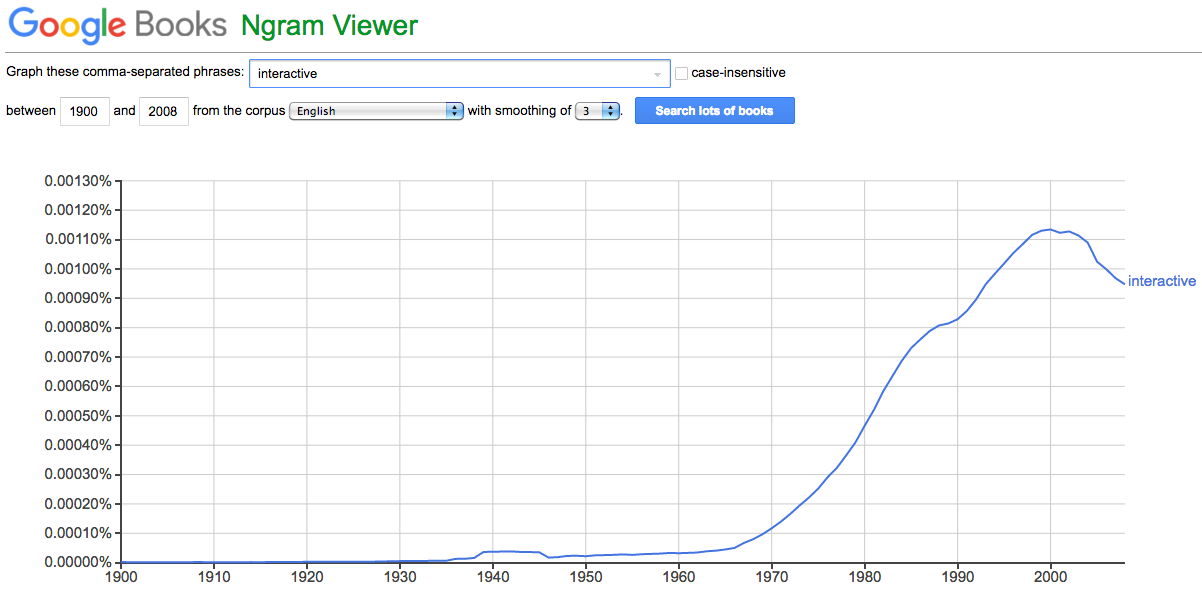

Interactivity is a relatively recent term that remains obscured by common usage. To put this into perspective, a quick search of interactive in the Google Books Ngram Viewer yields the following graph:

This graph is interesting because it parallels the increased alliance between art and technology from the 1950s onward. This alliance ushered in a new age of interactivity—one that becomes apparent when considering the emergence of television and video art in the 60s, for instance. Closed circuits made spectators integral to works of art in arguably unforeseen ways, and in doing so they required new descriptive words such as interactivity.

I believe we are in need of somethingmore than input in order to qualify what happens in an encounter with art as interactivity.

Given that my background in art history consists of knowledge of art post-World War II, this graph—while both interesting and revealing—is for the most part predictable. I say this because analog computing began to rise to prominence and be adopted by artists in the 50s, overwhelming support was given to the technological arts by backers such as Bell Labs in the 60s, and then—jumping ahead—interest in virtual reality experienced a rush in the 90s. Yet, for all its predictability and for all my familiarity with practices that have been loosely called interactive, I cannot give you a straightforward definition for the word. My hunch is that many others have stumbled over defining interactivity too and have opted for other words or descriptive phrases to use in its place as of late.

So, what do we mean when we say that something is interactive? And, in the realm of art, what may that something consist of? There are a number of examples and strata to be considered.

The spectrum of action & ‘live’ art

Unless we’re prepared to go down a philosophical rabbit hole, we typically do not regard the experience of viewing a painting in a museum as an inter-active one.

The painting is, by contradiction or negation, a categorical case of non-interactivity.

In our encounter with a painting we can say we are, at most, active as interpreters. When the object of visual art is a sculpture, we can describe our experience of it as being slightly more active than our experience of a painting, as we are enticed to walk around it. Put it outside, and we might even be drawn to touch it or climb on top of it. But, traditionally, in the gallery, what we see, we don’t touch; there is no inter to our action.

There is by contrast a significant amount of contemporary art that does invite our touch or, alternatively, our gesture. Much of it even goes one step further and responds to that physical input. Contemporary art of this kind is typically (but not necessarily) characterized as interactive by its use of software, or technology more generally. Therefore, addressing an example that involves both corporeality (or corporeal literacy) and human-computer interaction is essential.

Opposing the painting on the spectrum of interactivity is Ruairi Glynn’s Fearful Symmetry, an installation featuring a glowing tetrahedron that some would say “dances” with members of the audience. Glynn used an array of Kinect cameras—among other devices and materials—to create Fearful Symmetry, which was commissioned by the Tate Modern to inaugurate the London museum’s new ‘live’ art space, The Tanks, during August of 2012. FearfulSymmetry brings together robotics, interaction design, and gesturerecognition algorithms into an event of puppetry in which both the tetrahedron and its visitors take turns being the metaphorical puppets and puppeteers.

Participation as a governing factor

In between these endpoints — that of the painting and the robot puppet—there is a spectrum of other aesthetic works or practices that can be described as interactive with varying tenability. This spectrum has been theorized by computer art pioneers Stroud Cornock and Ernest Edmonds (1973) as consisting of the following categorizations or strata. Given the extensiveness and precariousness of what can be called interactive art, I take these to be neither mutually exclusive nor all-encompassing.

(a) The static system—the art object is unchanging, as is any traditional painting.

(b) The dynamic-passive system—the art object changes with time by the artist’s program or by factors in the environment; Dutch artist Theo Jansen’s wind-powered sculptures are great illustrations of this kind of system.

(c) The dynamic-interactive system—the art object is participatory: that is, it accommodates input from the participant. Many of Jeffrey Shaw’s installations, which are part kinesthetic and part digital or virtual, make an obvious case for such a system, but technology isn’t a necessity, as is demonstrated by Surasi Kusolwong’s participatory work which emphasizes social engagement.

(d) The dynamic-interactive (varying) system—a network in which the conditions of (b) and (c) apply, with the additional condition that the art object’s behavior can be changed through the modification of system specifications by a human or software agent (Schraffenberger & van der Heide 2012). This last strata is the most complex. It helps to imagine a dynamic-interactive (varying) system as capable improvising via learning & adaptation rather than just following a script.

With all the above strata in mind, it is possible to qualify the painting as “static” and Fearful Symmetry as “dynamic-interactive (varying),” with the varying element being Glynn’s behind-the-scenes team of software puppeteers who programmed the robot’s responses in real-time when they saw appropriate. The case of Fearful Symmetry is, however, a curious one. When deprived of human participants, we would expect the glowing tetrahedron to revert to being a static system rather than one which responds to factors in its environment.

Interactive public art, even when it uses strikingly similar mechanisms, functions differently.

A dog that runs in front of NAPA’s Blue Hour, like an unaware passerby, would technically elicit a response by activating motion sensors. It would, nonetheless, evoke the timeless thought experiment: "If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?" In other words, just because something is responsive doesn’t mean it’s interactive. Without establishing a feedback loop, an art object that affords participation but does not embrace that participation as a governing factor is not interactive. Carsten Höller’s functional playgrounds nicely expose this lack.

The supposed interactivity of augmented reality (AR) should hypothetically fit into the spectrum outlined above. However, because the categorization of AR is complicated by the possibility of considering either or both the augmenting interface and the objects in its real space of operation as the art object(s) or system(s), AR warrants a discussion of its own.

(Not) placing a finger on the concept of interactivity

While Cornock’s and Edmonds’ array of interactivity may help us plot contemporary art on a graph of interactivity based on the degree of human agency afforded, I believe we are in need of somethingmore than input in order to qualify what happens in an encounter with art as interactivity. And what that interactivity consists of is in need of conceptualization, not definition or distribution.

To put it another way, the spectrum explained above is in need of a conceptualization of interactivity that’s not wholly invested in a demonstration of technology’s mediating capabilities, but interested in the technology’s tweaking of lived experience and the reciprocal effect of that experience on technology—a back and forth of action and reaction. Thus, following Brian Massumi, I believe:

What is central to interactive art is not so much the aesthetic form in which a work presents itself to an audience—as in more traditional arts like painting, sculpture or video installation art—but the behaviour the work triggers in the viewer. The viewer then becomes a participant in the work, which behaves in response to the participant’s actions. Interactive art needs behaviour on both sides of the classical dichotomy of object and viewer. (2008)

One would not be wrong to interpret Massumi’s use of the term behavior, as having human(e) connotations. What Massumi is describing suggests that we forgo speaking of paintings, wind sculptures, and kinesthetic design when speaking of interactivity, and instead embrace works, objects, or systems that surprise us with properties that surpass mimicry and formulaic response with unexpected but relational feedback, as in Fearful Symmetry. In other words, the experiencer and the art object or system together should co-govern the interaction.

The something left to be desired

All in all, I think that the something more we need in a contemporary conceptualization of interactivity may be immediacy of presence (as in, let’s get rid of mediating interfaces that dilute our access to the object). Or some kind of communication—even coordination—which necessarily supposes a possible feedback loop that is predicated on a perpetual state of transitory open-endedness. This would make possible the emergence of otherwise unattainable properties that would make the happening a complete and iterative, but non-repeatable whole. And perhaps what that something entails, then, are the qualities of an event—a singular but passing occurrence that “has an arc that carries it through its phases to a culmination all its own: a dynamic unity no other event can have in just this way” (Massumi 2011). In this sense, I see installation art as advantaged, because it demarcates a special place in time and space.

Moreover, in any event of interactivity, I would expect not only social interaction among human participants, but also a mediating object—imaginably, with a liveness of some kind—that makes the event or the experience possible in the first place. Drawing from the artistic impulses of the 60s, this is a conceptualization of arelational aesthetics, but with technology at its center. It is a conceptualization that shines a light on the engineering of experience where engineering retains its mechanical connotations without manipulating human agency in such a way as to reinforce the subject-object binary. In this aesthetics, gestural and physical modalities are preferred over representational or linguistic ones, solely on the basis of their dynamism. For public art, an interactivity like this is key, because:

For art to switch its role from the private, exclusive arena of a rarefied elite to the public, open field of general consciousness, the artist [has] to create more flexible structures and images offering a greater variety of readings than were needed in art formerly. (Packer & Jordan 2002)

With a greater variety of readings, there may be greater chance for meaningful improvisation. And with this, we cannot go without reconceptualizing our notion of the artist in this approach to interactivity: it’s no longer necessary to assume that he or she has a particular craftsmanship, rather he or she is “a catalyst of creative activity” (Cornock & Edmonds 1973). As Bruno Latour (1996), speaking of puppetry, puts it:

If you talk with a puppeteer, then you will find that he is perpetually surprised by his puppets. He makes the puppet do things that cannot be reduced to his action, and which he does not have the skill to do, even potentially. Is this fetishism? No, it is simply a recognition of the fact that we are exceeded by what we create.